In the Studio with Anita Fields

By Chadd Scott on

Tulsa’s First Friday Art Crawl opens galleries, museums, and artist studios downtown from 6:00 to 9:00 PM on the first Friday of every month. Most of the artists working at the Tulsa Artist Fellowship’s Archer Studios (109 Martin Luther King, Jr. Blvd.) and greeting visitors are up-and-comers. One is a legend: Anita Fields (Osage/Muscogee; b. 1951).

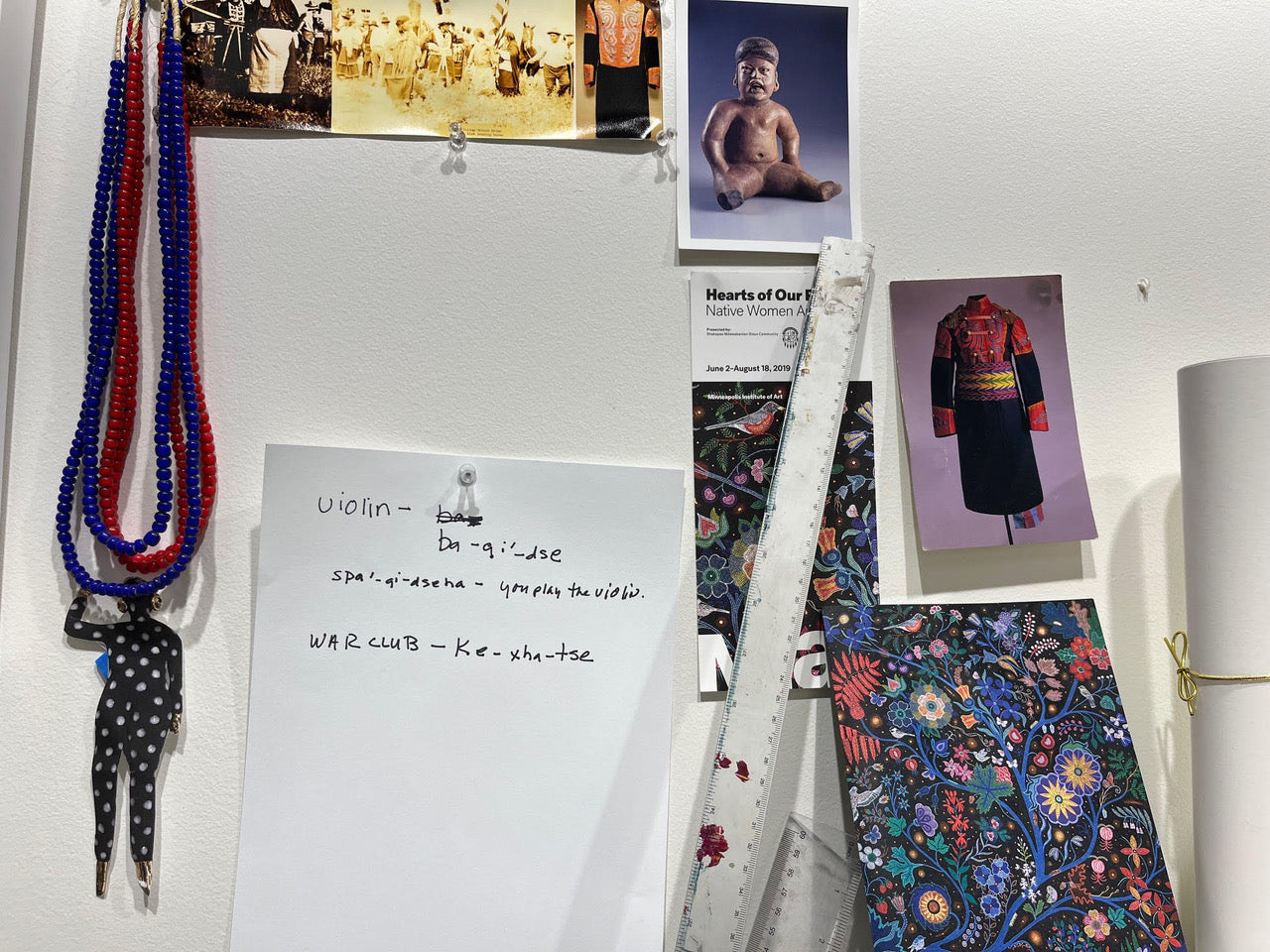

Close up look at items inspiring and informing Anita Fields inside her studio.

I visited Fields in her studio at TAF on the first Friday of May 2024. Our conversation centered on the time she spent at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe from 1972 through 1974.

IAIA had opened just 10 years prior as a high school and still wasn’t offering four-year degrees by the time Fields attended. In the subsequent 50 years, the school – the only fine arts school in the United States dedicated to the study of contemporary Native American art – has gone on to become one of the most prominent and prestigious in American art. As one example, Rose B. Simpson (Santa Clara Pueblo; b. 1983), Class of 2018, has major exhibitions and installations this year in Palm Beach, FL, Cleveland and New York, and is included in the Whitney Biennial.

Fields was convinced to attend by a cousin who had gone there.

“It was great,” Fields said of her first impressions upon arriving at IAIA. “It was so fun. Being around native people is fun, and you’re in Santa Fe and everything’s beautiful there.”

More than fun, Fields found a level of artistic support she hadn’t previously.

“Can you imagine arriving in Santa Fe and they open up these cabinets and go, ‘take any paint you want.’ It was like that,” she explained. “‘How big of a canvas do you want? We have a man who makes them for you, he'll deliver it in three days.’ It was like that. I got very, very spoiled.”

Then there was the clay.

“When I touched clay for the first time at IAIA, I was totally taken,” Fields remembers. She had some training with pottery previously, but experienced an epiphany at IAIA. “I don’t want to be a production potter, I want to take it further.”

She has.

Drawing on her cultural heritage in creating groundbreaking contemporary art, Fields has seen her work acquired by the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, AR, the Heard Museum in Phoenix, the Minneapolis Institute of Art, the Museum of Art and Design in New York, and the National Museum of American Indian in Washington, DC, along with being featured in countless major traveling exhibitions.

Inside Anita Fields' studio at the Tulsa Artist Fellowship.

Lloyd Kiva New

Field’s time at IAIA coincided with counterculture movements sweeping across college campuses in the U.S. The Red Power movement was stirring young Native people. The occupation of Alcatraz begun in 1969. The occupation of Wounded Knee in 1973. Nationwide anti-Vietnam protests.

At IAIA, this energy was magnified by being surrounded by other young, Indigenous creatives. With everything going on, Fields didn’t always put her studies first.

“I was pretty wild,” she admits. “Like being young anywhere else, but probably a little bit more amplified because we didn't have any folks looking over us.”

Wild enough to be expelled.

“I wasn’t going to class and acting up too much,” Fields said. “I was sent home because it was still very BIA (Bureau of Indian Affairs), old school, boarding school type of like – we're not going to have any of that and you're out of here if you can't march to the drum.”

Back at home, kicked out of school, hanging out, early 20s, it was IAIA Director Lloyd Kiva New who threw Fields a lifeline.

“He was in the painting studio – my friend was in there – and he goes, ‘whose work is this,’” Fields recalls being told. Her friend informed New he was looking at Anita Fields’ artwork. “He said, ‘where is she?’ (My friend said) she was released from school, and he said, ‘you get her back over here!’”

Not long after, a letter arrived at Fields’ home inviting her to return to IAIA.

“The underdogs, he wanted them there. He got me back,” Fields said. “Being an artist, there's part of you that is kind of like that, very rebellious. I'm going to experience all these things because I feel like I need to. I straightened up. It took me a while.”

It wasn’t the last time New would lift her up.

Years later, she entered her work to be considered for a show at the Southern Plains Indian Museum in Anadarko, OK. New was on the selection committee. When the committee met to discuss the applicants, Fields reintroduced herself.

“I'm sure you don't even remember me, but I was a student at the Institute,” she remembers saying. “He was so kind and generous and said this was my vision, that people would look into their backgrounds, look into their culture, and be inspired by it and start making contemporary works based on that. He said this is what it was all about.”

She got the show and a boost to her career.

“I know that he really believed in us, and he believed in what he was doing,” Fields said. “He was so far ahead of his time.”

Inside Anita Fields' studio at the Tulsa Artist Fellowship (2)

Role Models

Despite Fields’ rebelliousness, IAIA could still be intimidating for a young, female artist.

“IAIA was very male centric,” she said of the era. “The professors, and then of course the stars like T.C. (Cannon) and those guy painters, they were gods. Now it's kind of funny because when I think about it, it’s the women who stepped forward in the end.”

Early IAIA professors included Fritz Scholder, Allan Houser and Charles Loloma. Earl Biss, Kevin Red Star and Dan Namingha were among the early painters along with Cannon.

Taking nothing away from IAIA’s more recent male graduates, when the roster of women features Marie Watt, Cara Romero and Dyani White Hawk, it’s hard measuring up.

Fields first looked up to Linda Lomahaftewa (IAIA Class of 1965) – among the earliest IAIA students – then Jaune Quick-to-See Smith.

“In our native communities, there's very few and far between contemporary artists, so for you to meet up with a Native contemporary artist (was a big deal),” she said. “That was just so huge. I didn't know (if I could become a professional artist). It's the kind of thing that you think, ‘well, if they can do it, I believe there's a chance for me, that this is something that I really could (do).’”

Not only do, but do her way.

“In the formal training I had after (IAIA) – and a little bit before – I was never encouraged to look at my culture,” Fields remembers. “I would have professors say things like, ‘why do you keep doing that? That's irrelevant.’”

Representations of Native people and culture in contemporary art have always been relevant, they just haven’t always been appreciated. Thanks to Fields, New, IAIA, and its thousands of graduates and instructors, Native art and artists are now completely mainstreamed into the broader contemporary art world.

Fields will open her studio at the Tulsa Arts Foundation for visitors on first Fridays through 2024.